My wife is an English professor and although I'm a bit biased, she's an impressive teacher and I'm very happy to be her partner. In the last couple of years she came across a book, Specifications Grading by Linda Nilson, and our dinner conversations shifted to her new hope for how to motivate and assess her students. (We both enjoy these pedagogical dinner discussions--it's just one thing among many that makes our marriage so incredible.) Specs grading is a type of Standards Based Grading (SBG) and I have been interested in trying SBG for a long time. It seems to take me awhile to think about new ways of conducting my classes before I commit to the change, but conversations with her and the positive effects on her students made me even more interested to try SBG next year.

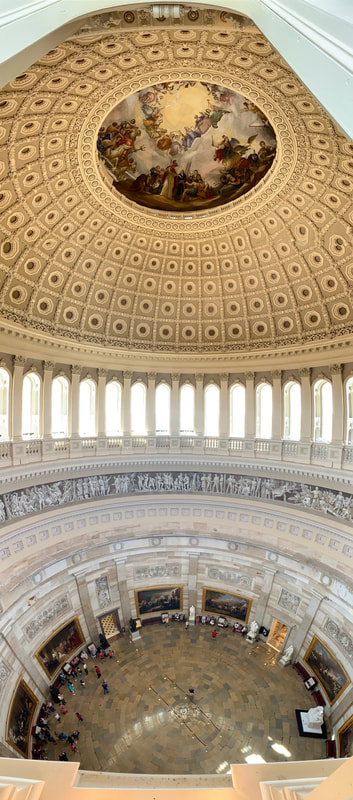

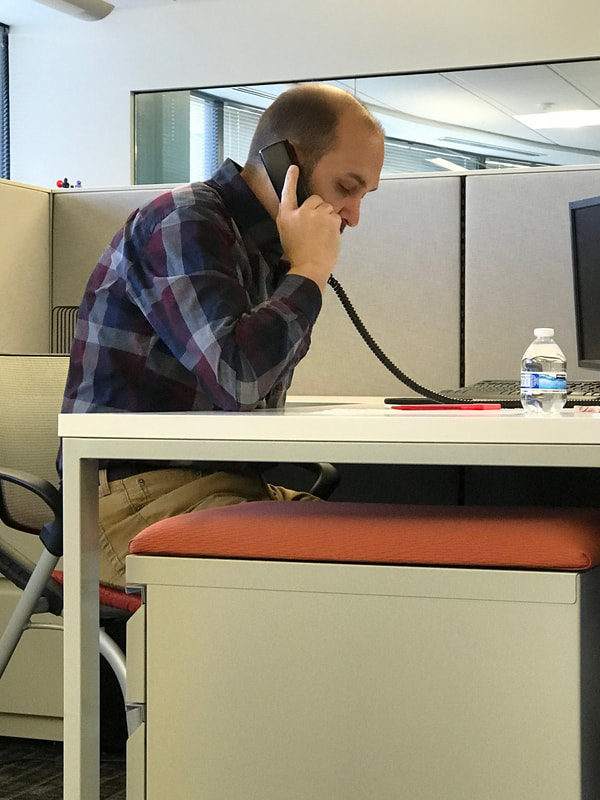

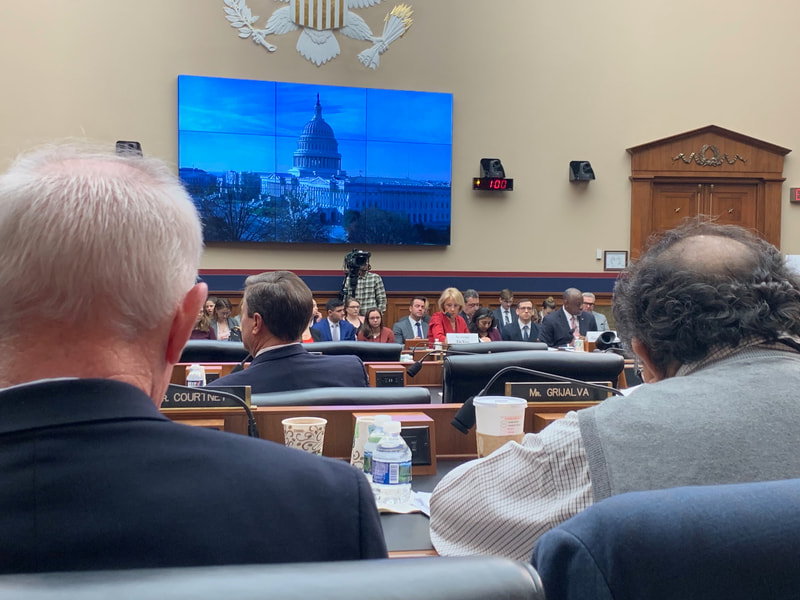

In addition to having a like-minded spouse, I have also been learning about how to employ modeling teaching techniques in my physics classes--many modelers use some form of SBG in their classes. Also, issues of equity in education are something that comes up quite frequently in my work as a Einstein Fellow in Congressman Raúl Grijalva's office on Capitol Hill. With those things in mind, when I heard Joe Feldman speak about his book Grading for Equity on a Harvard EdCast podcast, I knew I had to give his book a look.

In his book, Grading for Equity: What it is, Why it matters, and How it can transform schools and classrooms, Joe Feldman argues that grading is a challenging topic to discuss with teachers. Teachers' ideas of grading are wrapped up in our ideas about how learning occurs, motivation of students, self-direction, and control. Traditional grading practices (TG or TGP), for many teachers (myself included) often mean using a 0-100 grading scale with letter grades, grading homework and classwork for correctness, not accepting late work (or accepting it with a large reduction in credit), and one-chance summative quizzes and tests. Feldman argues that these TGPs are problematic for multiple reasons. I won't go over them all, but I would like to briefly discuss those that stood out to me.

With TG, mistakes are viewed by many students as "...unwanted, unhelpful, and deserving of penalty." Teachers using TGPs often judge students in all stages of learning including classwork and homework. This incentivizes students to hide their misunderstandings and weaknesses and can lead them to academic dishonesty / cheating. This is something I've personally observed in my classes and is a widespread concern among many teaching colleagues.

Tied up with TGPs is the idea that "points" can be used to motivate students to perform. Feldman says, "Teachers use "points" in grading based on the traditional belief that points motivate students to learn and behave, even though "one of the sturdiest findings in social science" is that extrinsic motivation for learning is ineffective and even harmful." Extrinsic motivation might work for repetitive and simple tasks, but it does not work well for conceptual understanding, flexible problem solving, or improving students long term interest and desire to learn. Feldman also argues that these TG point systems can also result in students that are more dependent on the teacher and therefore less independent learners. He also discusses the influence of conscious and unconscious teacher biases that can cause them to wrongly think that "motivating" students with points-based-consequences is the only effective measure they have with certain underrepresented groups. (This is particularly troubling and I highly suggest you read chapter 3 and follow his references.)

TG also hides or provides misleading information. In TG, a student's academic and behavioral performance over the course of a marking period are reduced to a single letter grade calculated via averaging all the student's scores. That single letter grade confuses and hides a student's true understanding of course topics and is affected by everything from a zeroes for missing assignments and homework scores that are due to a particular student's home environment and responsibilities outside of the school day. The mathematics of calculating the grade are inappropriate and problematic as well. (more on this in Part 2).

Teachers already know this. As the author writes, "Faced with the constraints of using a single letter to report student performance, teachers are forced to make creative adjustments and adaptations, making grades idiosyncratic, and, therefore, unreliable." The letter grades are subject to teacher bias--even if that bias is unconscious and unintentional. Feldman goes on to say, "The variance and unreliability of single-letter grades frustrate students, weaken the schools' professional community of teachers, and challenge the integrity of our schools."

Lastly, I was particularly intrigued by Feldman's analysis of TGPs in light of Carol Dweck's work on Mindset. I was introduced to Dweck's work in graduate school at the University of Akron and my thoughts on teaching have been affected by it ever since. (I expect you are already familiar with the basic tenets of fixed vs. growth mindsets as they are now common terms in educational circles, but if not, follow the link to learn more.) Feldman says that although many schools espouse Dweck's "growth mindset" ideals and communicate this to students by stating so in written and oral communications (bulletin boards, posters, course expectation sheets, emails, etc.), TGPs "...often communicate a dis-empowering "fixed mindset" framework for learning, add stress and uncertainty, and can result in students engaging in compensating behaviors." TGPs frame grades as "performance goals," that is a goal focused on external judgement and evaluation. This can lead to students being motivated only to take on and complete tasks seen as relatively easy and to avoid chancing failure in order to avoid appearing unable or not smart enough.

So then what to do instead? I'll write about the more equitable grading practices Feldman recommends (some SBG and some not) in my next post.

In addition to having a like-minded spouse, I have also been learning about how to employ modeling teaching techniques in my physics classes--many modelers use some form of SBG in their classes. Also, issues of equity in education are something that comes up quite frequently in my work as a Einstein Fellow in Congressman Raúl Grijalva's office on Capitol Hill. With those things in mind, when I heard Joe Feldman speak about his book Grading for Equity on a Harvard EdCast podcast, I knew I had to give his book a look.

In his book, Grading for Equity: What it is, Why it matters, and How it can transform schools and classrooms, Joe Feldman argues that grading is a challenging topic to discuss with teachers. Teachers' ideas of grading are wrapped up in our ideas about how learning occurs, motivation of students, self-direction, and control. Traditional grading practices (TG or TGP), for many teachers (myself included) often mean using a 0-100 grading scale with letter grades, grading homework and classwork for correctness, not accepting late work (or accepting it with a large reduction in credit), and one-chance summative quizzes and tests. Feldman argues that these TGPs are problematic for multiple reasons. I won't go over them all, but I would like to briefly discuss those that stood out to me.

With TG, mistakes are viewed by many students as "...unwanted, unhelpful, and deserving of penalty." Teachers using TGPs often judge students in all stages of learning including classwork and homework. This incentivizes students to hide their misunderstandings and weaknesses and can lead them to academic dishonesty / cheating. This is something I've personally observed in my classes and is a widespread concern among many teaching colleagues.

Tied up with TGPs is the idea that "points" can be used to motivate students to perform. Feldman says, "Teachers use "points" in grading based on the traditional belief that points motivate students to learn and behave, even though "one of the sturdiest findings in social science" is that extrinsic motivation for learning is ineffective and even harmful." Extrinsic motivation might work for repetitive and simple tasks, but it does not work well for conceptual understanding, flexible problem solving, or improving students long term interest and desire to learn. Feldman also argues that these TG point systems can also result in students that are more dependent on the teacher and therefore less independent learners. He also discusses the influence of conscious and unconscious teacher biases that can cause them to wrongly think that "motivating" students with points-based-consequences is the only effective measure they have with certain underrepresented groups. (This is particularly troubling and I highly suggest you read chapter 3 and follow his references.)

TG also hides or provides misleading information. In TG, a student's academic and behavioral performance over the course of a marking period are reduced to a single letter grade calculated via averaging all the student's scores. That single letter grade confuses and hides a student's true understanding of course topics and is affected by everything from a zeroes for missing assignments and homework scores that are due to a particular student's home environment and responsibilities outside of the school day. The mathematics of calculating the grade are inappropriate and problematic as well. (more on this in Part 2).

Teachers already know this. As the author writes, "Faced with the constraints of using a single letter to report student performance, teachers are forced to make creative adjustments and adaptations, making grades idiosyncratic, and, therefore, unreliable." The letter grades are subject to teacher bias--even if that bias is unconscious and unintentional. Feldman goes on to say, "The variance and unreliability of single-letter grades frustrate students, weaken the schools' professional community of teachers, and challenge the integrity of our schools."

Lastly, I was particularly intrigued by Feldman's analysis of TGPs in light of Carol Dweck's work on Mindset. I was introduced to Dweck's work in graduate school at the University of Akron and my thoughts on teaching have been affected by it ever since. (I expect you are already familiar with the basic tenets of fixed vs. growth mindsets as they are now common terms in educational circles, but if not, follow the link to learn more.) Feldman says that although many schools espouse Dweck's "growth mindset" ideals and communicate this to students by stating so in written and oral communications (bulletin boards, posters, course expectation sheets, emails, etc.), TGPs "...often communicate a dis-empowering "fixed mindset" framework for learning, add stress and uncertainty, and can result in students engaging in compensating behaviors." TGPs frame grades as "performance goals," that is a goal focused on external judgement and evaluation. This can lead to students being motivated only to take on and complete tasks seen as relatively easy and to avoid chancing failure in order to avoid appearing unable or not smart enough.

So then what to do instead? I'll write about the more equitable grading practices Feldman recommends (some SBG and some not) in my next post.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed